Image credit: Auto Imagery

Image credit: Maddie Short

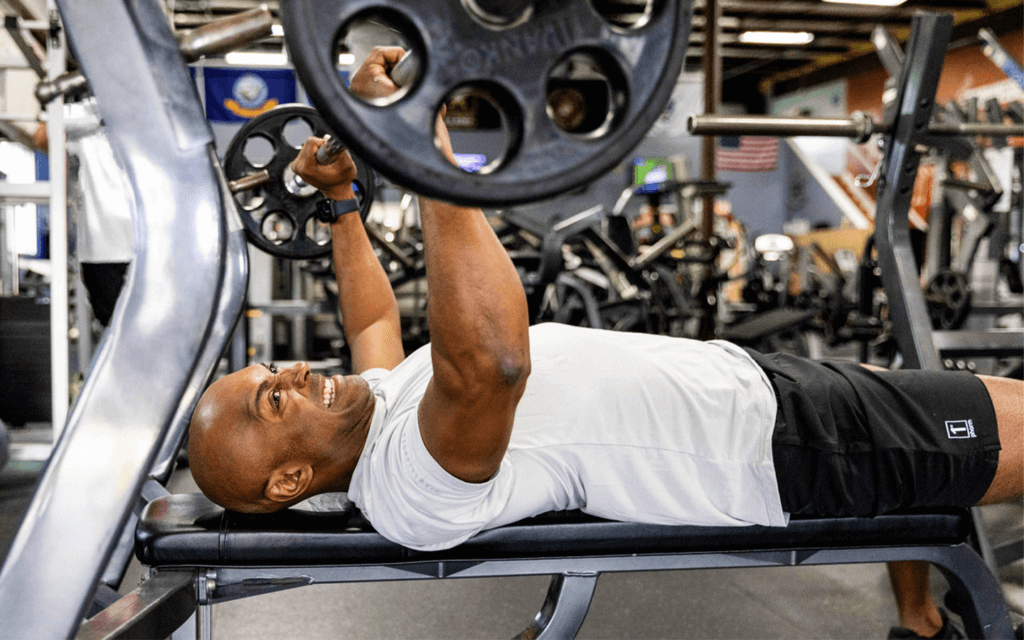

Antron Brown’s legacy goes beyond competition.

A drag racing legend, team owner, mentor, father, husband and spokesperson, Brown has weaved the core elements of his life together to mold the man he is today.

Any other athlete boasting 790 round wins, 71 event wins and being crowned the Top Fuel Driver of the Decade would feel the need to boast.

Not Brown, who speaks with the tone and grace of a rookie simply wanting to make the fans who flock to see him in the paddock, leave with a smile.

“A lot of my peers and people I have raced with always say, ‘AB, everybody loves you.’ And I go, ‘Well, they love me because you have to give them love for them to love you in return.

“I think that’s the one thing that’s so easy to give. Many people treat people for who they are – their status – and for me, I don’t care who you are, where you come from or what you do. I cherish each and every person around me. I show them kindness and love every day.

“I’m just a normal guy who is a fierce competitor on the track. I brought my happiness and gave them experiences in life that they can hopefully share with others.”

The long list of “experiences” is punctuated by three Top Fuel Championship wins in the 2010s, a fairytale dream for a guy with racing in his bloodline, and the potent scent of fuel coursing through his veins.

Now into his second season as owner and driver of AB Motorsports, Antron Brown’s passion and desire to succeed in the sport and leave an imprint on those he interacts with is as vibrant as ever.

An unwavering work ethic

“You could have anything in life as long as you work. Can’t nothing stop hard work. Nothing.”

These words laid the foundations for Antron Brown’s success today, paved his path, and cemented in him a relentless drive towards a life far from the one his grandfather endured.

His Grandfather Albert Brown grew up in different times, coming from a very poor family against the backdrop of the Depression of the 1930s. Set against the landscape of Chesterfield Township, tucked away in the north of New Jersey, just shy of 40 miles outside of Philadelphia – it was a time in which Afro-Amercians suffered the most.

The resolution of World War II was the catalyst behind the end of the Great Depression, with the shortage of war-related industrial jobs now becoming available to Afro-Americans. Higher wages, greater learning opportunities, and a chance to make more money offered a ladder to climb out of the long-accustomed poverty-stricken conditions.

A new dawn was also sprouting in the state’s race relations, with the war creating a “climate that strengthened the resolve of New Jersey blacks to struggle against the racial injustice at home.”

It was a time of change for Albert Brown, who, despite the struggles, put in the work.

In 1956, he founded Albert Brown Septic Tank Service, a company that offered minor excavating around houses in the local area, fitted septic tank systems, serviced them, and pumped them. The business, and his legacy, still live on to this day.

“My grandfather taught my dad and my uncle about hard work and sacrifice, and that same mentality is what I grew up around.”

A history of excellence…

As a young child, Antron Brown would quickly realize a love of sports, admitting to participating in “every sport there was.” His first endeavors were in Tee-Ball, no doubt excelling like Albert, who almost turned professional in Minor League Baseball before playing soccer and basketball.

Brown’s natural speed, once again passed down from Albert, who was fast on his feet, led him to the world of Track and Field, a path he would find himself close to following later in life.

“My family did various sports but were always top tier in our state. I was the same way. No matter what I chose to do, I was always one of the top players in every sport I played.”

At age six, he moved to his grandmother’s 10-acre farm, opening him up to the world of cars. He would be a regular at his father and uncle’s races on a weekend, the pair competing at the sportsman level at New Jersey tracks. Eager to learn about the family business, Brown would get involved.

Like many of the sports previously mentioned, he took to racing much the same, highlighted by the fact he first operated a motorcycle at the age of four.

Some people are born talented, leaning on the genetics passed down to them from elite family members, but Antron Brown dismisses the theory that he was part of this group, simply noting his success to his “work ethic.”

“The funny part is that it wasn’t from skill. I just loved to compete, no matter what it was. I never had time to sit still. I didn’t know what sitting still was like, I was always doing something. For me, that was something that was just ingrained into me from my family because we all competed against each other.”

Brown was contracted into an unspoken competitive deal that would shape his future. He would compete against his dad and uncle at horseshoes, racing dirt bikes, or basketball. “If not, we were foot racing in the field. They would say, ‘Come on, see if you can get me now’, and I will never forget that.”

Call it stubbornness or an obsession with winning, Brown would not be beaten twice at anything.

“If somebody did get the better of me, I looked at them like, you won this battle, but wait until next time.I went home and got to work. If I was playing basketball with my strong right hand, I said, I’ve got to learn how to be good with my left. So I only played people that weren’t better than me with my left hand. I always worked on all my weaknesses to make them my strengths.”

The need for speed

Speed was Brown’s soundtrack growing up, accompanying him throughout his days at Northern Burlington County Regional High School, where he was a standout sprinter and long jumper for the track and field program.

Upon graduating, he opted to jump straight into a professional Motocross career before a bad injury forced his hand, dealing with his decision to move to Mercer County Community College. Brown would earn an Associate of Arts degree in Business Administration, but his star turn as a track and field icon for the Vikings’ team turned heads.

New Jersey already had the recognition of fostering the talents of Carl Lewis, the nine-time Olympic gold medalist sprinter who was raised just 30 minutes from Brown in Willingboro.

“Our whole area was known for track and field because of Carl. I was one of the fastest kids in the state and got a full scholarship. Athletes were coming from overseas from the likes of Jamaica and Trinidad, but I ended up being the fastest kid on the track team, period.”

The statistics back up Brown’s claims. At one point, he was ranked number one in the country for the 55-meter indoor dash, running the now-defunct distance in 6.27 seconds as a freshman before clocking in a 10.2-second time for the 100-meter.

Unsurprisingly, he was soon in contention for the big leagues, receiving invites to preliminary events and trials to run in the holy grail, the Olympics. Long Island University swooped in, offering Brown a track scholarship, but his eyes were always wandering, flirtatiously glancing over at his true love, racing.

Brown never followed in the footsteps of Lewis, who won gold medals at the Los Angeles, Seoul, Barcelona, and Atlanta Olympics from 1984 to 1996. But, the experience played a fundamental role in his development.

“The Mercer track program influenced me. When I was working with (then-coach) Frank Squibb, he taught me how to dedicate myself and work hard. It wasn’t high school anymore. We actually had real workouts – it was like work. I remember waking up at 5 a.m. for training.”

Squibb, who went on to coach at Widener University, added, “Every athlete I have coached since Antron has had to meet the level of professionalism for a college athlete that he helped set in my mind.”

The world of track and field missed out on Brown, who, in his heart, knew life in racing was his true calling – a career he started at age 12 – and after a call from former NFL cornerback Troy Vincent, his ascent to the top began.

Vincent, playing for his hometown team Philadelphia Eagles, fulfilled his need for speed in 1998 by fielding a Pro Stock Motorcycle team in NHRA Winston Drag Racing Series and AMA ProStar competition.

His first move was to headhunt Brown, his wife’s cousin, offering him the chance to ride for his drag-racing team, Team 23, named after the number Vincent donned on the back of his Philadelphia jersey.

In April 1997, Vincent offered Brown a chance to ride for the drag-racing team he was building. Brown wasted no time proving he was worthy.

On his first trip down a dragstrip, Brown recorded an elapsed time of 10.20 on Vincent’s modified Suzuki GSXR street bike during a test-and-tune session in May 1997 at Atco Raceway in Atco, New Jersey. He then dropped into the 9.40-second range at 150 mph later that month and then, in June 1997, attended the Frank Hawley Drag Racing School in Gainesville to take the first step toward earning his NHRA Pro Stock Motorcycle license.

After earning his NHRA license in June 1997, the team began extensive testing with a fresh-faced 21-year-old Brown. Vincent, who rode high-performance street motorcycles in 1990 before moving to a career in the NFL, said he was “living his dreams through Antron” and “a great kid.”

A typically level-headed Brown, fuelled by the same competitive streak that consumed him while playing horseshoes with his father and uncle, coined it as the “opportunity of a lifetime.”

Little did Brown or Vincent know, a long journey of success lay ahead.

“For me, that’s where I wanted to go and what I wanted to do. And it’s what I dreamed about since I was a kid.”

Double the wheels, double the fun

From 1998 to 2007, Brown collected 16 victories and twice finished second in the standings in Pro Stock Motorcycle in 145 events, ranking him 11th in the all-time leaderboard for most wins.

With his stock rising, Brown began putting the feelers out about jumping to Top Fuel Drag Racing. “I learned throughout my career the squeaky wheel gets the grease. You’ve got to let people know what you want to do.”

After joining the Don Schumacher Racing team in 2002, Brown’s potential to switch to Top Fuel cars soon flickered in the mind of crew chief Lee Beard. Described as resembling a “young Bruce Dern: thin, entirely grey, diminutive silver mustache” with “brown eyes” that “often appear black” and a demeanor that is “as intense as your average serial killer”, Beard spotted something in Brown.

“Lee was crew chief at the Matco Tools team after he left Don Schumacher, and I had a great relationship with him. He always told Don, “This kid will be good in the race car. He’s good with the fans and a great spokesperson and role model.”

Schumacher was not convinced, and it wasn’t until Beard got a job with David Powers Motorsports did the wheels start turning. “Lee saw the desire I have for racing. I love racing, and I love competition. Lee saw that and asked me one day if I ever had an interest in wanting to race a nitro car. Naturally, I told him I would love to give it a try one day.’’

Brown was brought on board by Beard and Powers on an initial six-month program to learn his trade before the racer put himself through Frank Hawley’s Drag Racing School to prepare him for the next stage of his career.

“I needed to prepare myself. I did the class below Top Fuel, Alcohol Dragsters, and when I did that class, I was just learning the craft of what I needed to do and how I needed to do it. I was doing mental reps in my head after I got my license, so when I sat in the Top Fuel car, I had already done 1,000 mental runs.”

This set up Brown for his test session with the team. “I got three laps. I went down the track, then came back, taking infancy steps. When I got out of the car, Lee looked at me and went, “If I didn’t know that you’d never driven a car, I would’ve sworn you’d been racing for years. You look like a trained professional.”

The penny dropped. Brown got a call from Matco Tools Top Fuel a week later.

“That’s when my Top Fuel career started. When I stepped in, I gave it all I had. I ensured I was prepared for that opportunity to cease and grab hold of it. It took me around four to five years to reach that point, but I never gave up on my dreams or myself. That’s what got me there.”

In the space of ten years, Brown went from two wheels with handlebars and 600 pounds, including rider, into four wheels, some 2,225 pounds and 7,000 horsepower and a long, sloping needle nose to travel the quarter-mile at a speed of over 325 mph.

A nail-biting moment in history

When he finally did make the jump, Brown’s natural aptitude made others wonder if he was a true rookie or a veteran of the category. Driving the 10,000-horsepower machine was practically second nature to him.

Brown finished fifth, third, fourth and third in his early seasons in Top Fuel, showcasing the natural flair and potential that Beard spotted almost a decade earlier. In 2012, Brown was ready to make history.

A dominant season followed, with Brown and the team not losing one round of the first 24 races. A comfortable first championship loomed; however, life isn’t always that straightforward. “The last two races of the year, we lost the first round.

“The race before, our management box took a dump, and my car shut off going down the racetrack, then we lost against the number 16 qualifier because my car shut off. In Pomona, California, all we had to do was win the first round. We took off, and my fuel line busted off the car.

“Anything that you could think could happen happened. The worst luck that you could ever think of in your life.”

Brown came into the season final leading the the-seven-time world champ Tony Schumacher by a seemingly comfortable margin of 65 points. After the fuel line disaster, Brown suffered minor burns and the painful reality that one of Spencer Massey or Schumacher could pip him to death.

Massey was soon out of the running, but Brown and his team stood nervously on the starting line, watching his once seemingly insurmountable lead being erased 20 points at a time, hoping to see anyone stop Schumacher and history from repeating itself. Only one man could save Brown. Brandon Bernstein.

“Brandon and Tony didn’t have good chemistry. They were rivals. Tony always talks junk against Brandon, and Brandon doesn’t like him, and they’re racing each other. I’ll never forget that Brandon didn’t have the car to win the final. His car was running well, but Tony had the US Army car, which always won World Championships.”

A round before the final run, Schumacher had outrun Bernstein by four-hundredths of a second. It seemed inevitable that only one conclusion would unfold.

“When you go through a moment as we had, there’s nothing you can do but sit and watch. It felt like being a kid in elementary school when days felt like 30 hours long. You’re watching people race and can’t do anything about it. I felt like we had a 30% chance.”

Miracle comebacks were a specialty for Schumacher, overcoming larger deficits with one race remaining in both 2006 and 2007, respectively, but when the lights went out, Bernstein came up with the unthinkable.

Both cars made flawless passes beneath the darkened California sky, Brown and his team holding their collective breath before, in the blink of an eye, the win light lit up in Bernstein’s lane, taking a photo finish victory by a margin of by eight-thousands of a second.

It was his first win in three years, securing Brown’s first series Championship.

“It was pandemonium. I looked in awe. My wife was near me. My wife’s jumping. Everybody’s screaming around me. And I’m looking like, “We just won. We just won our first championship.

“My crew chief Brian, he’s like 6 feet 2 inches, a big muscle man. You can see tears coming from his eyes. All the guys are tearing up, and I’m just in awe. I don’t know what to say. I’m speechless. My heart just stopped. The emotion was crazy. I start jumping.

“I was hugging my wife so hard… she’s only 5 feet 2 inches. I think I had her in a headlock because her head’s right here in my arm. And I’m choking her to death because I’m so excited. And she’s looking at me; she can’t breathe.

“It was one of those moments that I remember like yesterday.”

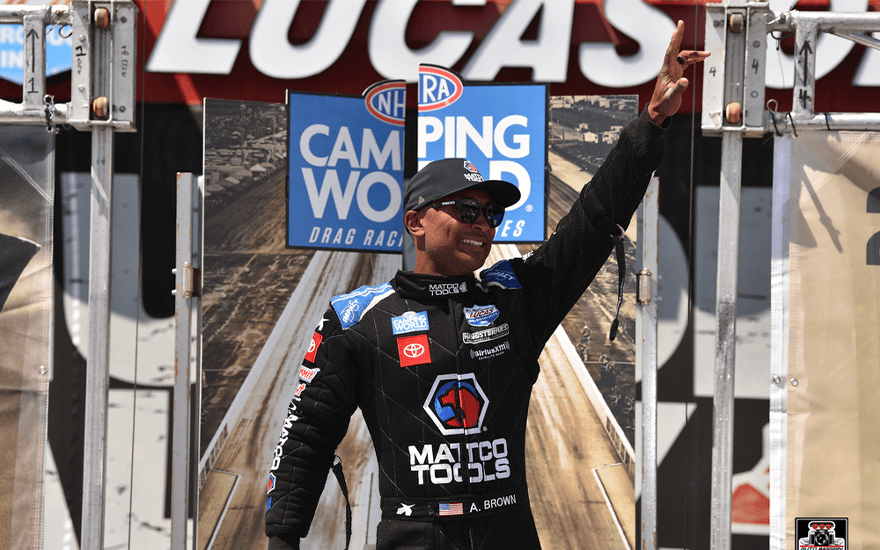

The win also made Brown the first African-American champion in any NHRA pro series, but Brown feels the win went beyond just his race. “I’ve never looked at it as just being an African American. I was truly blessed by the family that I always had around me and the way I was raised through my grandpa, my dad, my mom and everybody around me.

“It was one of those feelings that were awesome. Because here’s this kid out of Central New Jersey living his dream.”

For Brown, it was all about being a motivating force for kids worldwide, no matter their background, race, religion or social standing. Proud of his family roots, it’s clear his childhood was the main driver behind his writing his name in history books.

“My family had their own business. My mom worked at the post office. My dad was in the National Guards. They worked for everything that they had, and took advantage of every opportunity by being prepared for it, to grab and hold onto it.

“If he can do it, I can do it.”

Cementing legendary status

2012 signified a milestone moment in Brown’s life, and he soon followed in the footsteps of his idol, the iconic “Big Daddy” Don Garlits, a man who pioneered the sport and earned a spot in the hearts of drag racers for decades to follow.

In his 40-plus years behind the wheel, Garlits accomplished more than just racetrack victories. The dragster icon broke numerous speed records and revolutionized the niche motorsport with innovative designs and applications.

He forged a four-decade career in top fuel competition, winning 144 sanctioned events and three NHRA championships in 1975, 1985 and 1986.

“He was just a faith-driven man. He put God first, and everything else came from behind, and he was a multi-time world champion in NHRA drag racing. He’s literally the king of our sport, period. And he’s known around the world by a lot of people.

“If I can be one of those types of mentors or somebody that people look up to, that’s what it’s all about for me.”

Brown’s admiration for Garlits stemmed from an unexpected encounter in his childhood. Attending his first-ever National event in Englishtown, New Jersey, his family had taken him to see the big guns of Pro Stock Motorcycles.

An awe-struck Brown, reveling in a place that felt like home, was meandering through the sea of bodies when he caught the eye of none other than the man himself, Garlits. The young, bright-eyed racer, with dreams of following in his hero’s pedal-scorched footsteps, had one question.

“Why they call you ‘Big Daddy’. You don’t look that big to me!”

Brown recalls Garlits’ reply as if it occurred mere minutes previously. “Cause I’m big in heart, son.”

Six words imprinted on Brown’s life, and, in a romantic turn of events, Garlits has been his mentor throughout his career, always willing to offer advice and pass on his unmatched expertise over the phone.

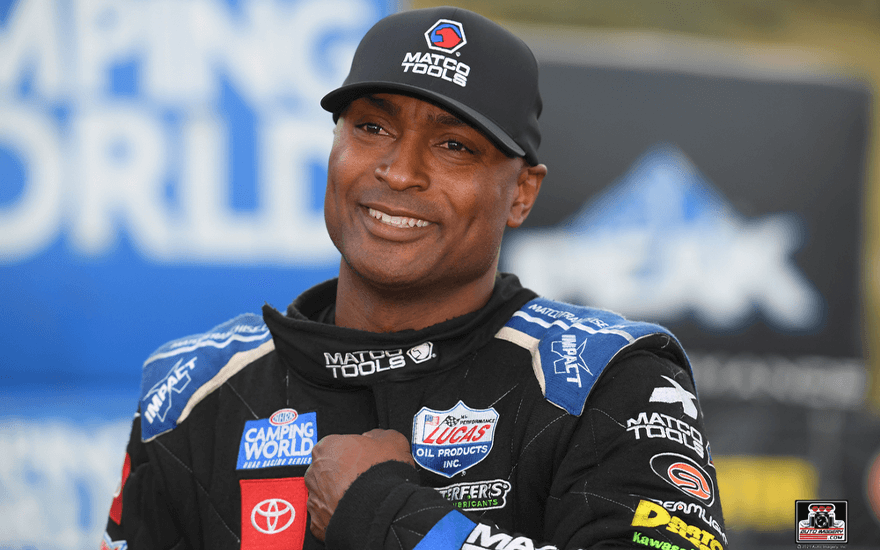

Throughout the 2010s, Brown, guided by Garlits, though he may not admit it, began to cement himself as one of the greats, creating a legacy that expanded beyond his seat behind the wheel.

Championships in 2015 and 2016 followed his dramatically clinched debut crown, asserting a level of dominance that was unmatched for seven years, the previous time a racer had won back-to-back titles.

Despite a quieter end to the 2010 era, in which Brown took home just one Wally – a trophy awarded to winners of an NHRA national event – over the 2018 and 2019 seasons, his success and dedication to the sport earned him the accolade of Top Fuel Driver of the Decade.

Upon receiving the recognition in 2019, Brown said, “The crazy part for me personally is I have never looked back at what I’ve accomplished. I’m always looking forward to what else I can grasp. I’m in the middle of my career, I’m still strong, and I’m still fighting. I’m always looking to be better. That’s what you have to strive for.”

Four years later, Brown is still racing, still competing, and still doing it with a smile on his face.

The only difference is who he is racing for. Introducing AB Motorsports.

Owning his future

Perhaps it was inevitable Brown would eventually pioneer his own team. Despite the difference in trade, there are distinct parallels between him and his grandfather, Albert. Both were raised on hard work and an undying desire to go beyond the limit to achieve great things.

Brown is motivated daily by his family members, who still run the septic tank business, which opened in 1956. He once joked that he didn’t want to join the family trade because he didn’t want “to be No. 1 in the No. 2 business.”

It was time for Brown to parlay all of his own lessons and observations, all of the wisdom and data Don Schumacher had shared with him in frequent one-on-one meetings, and all the advice from trusted friends – Vincent, Beard and Garlits, to name a few – and step into team ownership.

A major speedbump delayed his grand plans, with the pandemic pushing the launch of AB back by two years. While Brown had locked in several pre-existing sponsors, financial restrictions made it almost impossible to cultivate and grow new relationships. Ordering parts and car pieces proved a mammoth task due to manufacturers’ shutdown.

Call it superbly timed planning or a stroke of foreshadowing fortune, Brown had begun to lay the foundations in place during the 2019 season while still competing for Don Schumacher Racing. “I ordered stuff way in advance, and was looking at what was needed, how to get it, and go after it.

“Still, with all the proper planning, we fell short on some things, because you couldn’t just ring up and get them. It was a tough start, but now we are fluent and starting to balance things out into a healthy routine.”

Schumacher was “very supportive” of Brown’s endeavors ahead of his team launch in 2022. Brown has modeled himself on a pearl of wisdom provided to him by the Hall of Famer: “You don’t have to be the smartest, but you can’t be the dumbest, either.”

Part of Brown’s motivation for starting a team is not only providing opportunities to talented people but also being part of the next generation of owners. For quite some time now, Brown has thought about the need for people to keep the sport going when folks like Schumacher, or John Force and others are no longer around.

“Hopefully, I can motivate some people out there to say, “Hey, AB’s doing it. I can do it.”

Brown knows all too well about the fine margins of drag racing in the hot seat and believes that to be the case as a team owner. “You’ve got to do all these small things to stay ahead of the competition. We win and lose by a thousandth of a second. If you focus on all the small things and get a handful of them, you have a really good advantage.

“You take that advantage to the bank, and it’ll start paying off dividends where it can start plucking off round wins. Those round wins turn into race wins, and race wins turn into championships.”

It was almost the fairytale start for Brown and AB Motorsports. Sitting in 12th, Brown and his team went on a stunning run that elevated them to 6th in the overall rankings, eventually jumping to 2nd and finishing a mere 62 points behind Brittany Force.

“It was a great story, because we came from the outside looking in. We lost the championship by less than a round of racing.”

The team’s performance optimized Brown’s career.

He outworks his competition, a trait that has been instilled in him since galloping through the fields at his grandmother’s ranch, attempting to navigate away from his chasing father and uncle.

While others sleep, Brown is working. Figuring out ways to gain that title-winning inch. Mistakes will be made – Brown is aware – but he is happy to make them, learn from them, and get over the hurdles.

AB Motorsports sit 9th after underwhelming performances at Gainesville and Arizona, but Brown will take stock, learn, adapt, and come back stronger.

Simply, because that’s what he does. It’s what he has always done.

Most importantly of all, he does it with love.