“More people have been to space than skied to the South Pole unsupported.”

The enormity of the task ahead of Sam Cox is inconceivable.

2000 km across the frozen and barren Antarctica with nothing but his own wits and a pulk containing his life source for 75 grueling days of mental and physical extremities.

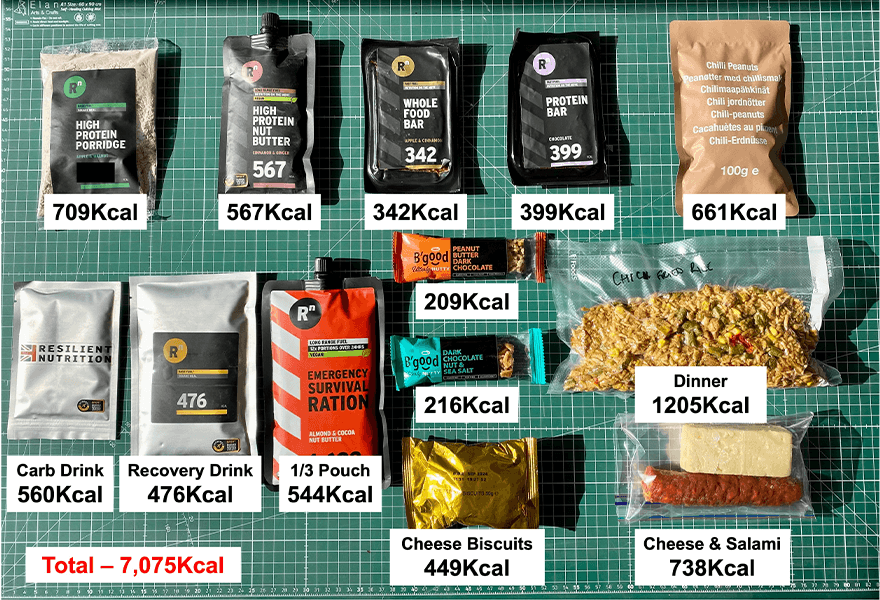

Using skis to aid his movement, the South Devon native plans to eat 7,000 calories daily, with 24 hours worth weighing in at 1,427 grams.

Surviving on a diet mainly centered around the consumption of Resilient Nutrition High Protein Porridge, Nut Butter, Cheese Biscuits, Salami, and Protein Bars, Sam Cox’s quest is fast approaching.

Sam Cox is expected to arrive at the coast of Berkner Island—an ice rise discovered under the leadership of Captain Finn Ronne of the United States Navy Reserve during the 1957-1958 season—in November ahead of a monumental test of endurance.

He’ll be away from his wife, Abi, and their four-month-old daughter, over 10,000 miles from his home in Torquay and isolated from human life for two-and-a-half months.

Sam will miss his child’s first Christmas. Alone. Just himself and the elements witness temperature drops exceeding -40 degrees Celsius.

“I think, in hindsight, it was my way of coping with lockdown,” Sam Cox told Muscle and Health.

“I’ve always enjoyed a goal and a project to work on. Regarding people who have been to Antarctica, less than 50 people have skied to the South Pole.

“It’s generally one of the last places we can still fully understand. There’s a reason why no permanent people live there.”

Fresh from a trip to Leeds Beckett University, where he underwent a V02 max and lactate threshold tests and a stint in the cold chamber, Sam’s final preparations are well underway.

Admin duties, equipment checks, and final tweaks to his meticulously organized nutrition schedule are wedged between his job working for Resilient Nutrition and press appearances with Sky News and the BBC.

If he successfully reaches the base of the Reedy glacier on the Ross ice shelf following Antarctica’s longest solo unsupported ski crossing, the name Sam Cox will be in the record books.

He doesn’t like the word legacy, but a legacy is what he will leave.

Sam spoke to Muscle and Health about his mammoth expedition and the various trials he was expecting to encounter on the world’s seventh continent.

You’re trekking 2000 km across the vast wilderness of Antarctica, a distance no one has ever skied without support before. The big question is why?

“The idea was a lockdown thing. I was away with the military then, so COVID wasn’t a thing when we left the UK at the end of January. It was ninth in the news, and this weird thing is happening in China.

“I went to Southeast Asia for an exercise where we had no contact or phone signal.

“Suddenly, we went from being busy and then getting pulled off the exercise to being told we’re going back to the UK tomorrow morning.

“I was back home on Saturday, and then the UK went on lockdown that Monday.

“It was pretty nice for the initial week or two of not doing anything, but I quickly got bored. My wife’s physio was changed to the COVID ward, so she was busy.

“She was returning frazzled, and I felt restless because she was so busy and I wasn’t.

“So, I came up with the idea (of the challenge) and started looking into it. It escalated from doing something like a marathon to an ultra-marathon to trying to do something more gnarly into what it is now. It escalated!

“I went back to work after a few weeks, and then the second lockdown came in, and I was just as bored, so I thought, ‘screw it,’ I’m going to do it.

“Once you tell a few people you have committed, and once you tell your parents, and they’ve told 500 people as my mom does anyway, you have to commit to it.”

Had COVID not hit the world and lockdown not happened, do you think you would be preparing for this trek, or was an adventure like this something you always saw yourself going for?

“No, COVID is the main thing. I have always been professionally driven since I joined the Royal Marines. All my goals since I joined in 2010 were professionally guided.

“If I wanted to complete a course or I wanted to pass something or do a specific role, you train for it, and you put your mind to it, and you get to the point where you achieved it, did the job for a bit and then you’d move on to the next one.

“That’s just the nature of the way the Marines work.

“I was happy doing that professionally for quite a while. COVID was the first switch, which made me think everything I have done is professional and it could be better for me as an individual. My planning was all done on someone else’s timeline.

“This was the primary switch. I wanted to do something for myself.

“Something like this may have happened, but I don’t think it would have happened now. It could have been in 10 years.

“COVID changed a lot of things for a lot of people, and for me, realizing that the military is coming to its end for my professional career was the beginning.”

You’ve said your gateway moment for your adventures was back in 2006 when you completed Ten Tors, a 55-mile trek across some of Southern England’s most challenging terrain and highest peaks. Why was that moment so significant for you?

“The event was on my doorstep as a teenager and was a sense of achievement. It’s that goal. I’ve always preferred getting hands-on and doing things.

“The first one was 35 miles, which I did as a 13 or 14-year-old, and that was the gateway to push on to the 45 and 55 miles editions. I liked doing the work, and that’s where the idea to join the Marines kicked in as a 15 to 16-year-old.

“I enjoy being outside and the sense of accomplishment, as well as the training to achieve a long-term goal and the build-up for it.

“You don’t just achieve it.

Many people don’t necessarily see this with things like this Antarctic expedition. They need to understand the process has been nearly four years by the time I finish.

“Four years of planning, training and background research.”

You joined the Royal Marines in 2010. What did that experience teach you about life, and did it help to instill the mentality you have today?

“It’s 13 years of applied resilience. The phrase we always got told in training was ‘expect the unexpected.’

I remember we had a three-week-long exercise before going on it, where they muck around for the whole weekend.

“On a Friday afternoon, we got told we were now on this exercise, and we had to answer the phone within the three weeks, but they will call up at two in the morning, and then you get told to report to a lecture theatre.

“You’ll watch a war movie video, and they make you take a test afterwards.

“You learn to deal with stuff that just gets chucked to you, which is what you need, significantly as a soloist doing things like this if conditions or something will change.

“It’s about having the confidence to go and embrace change.

“Physically, it has taught me a different level of fitness.

“It’s not like going to the gym for an hour daily. You can be an athlete and physically fit, but you’re very focused on what that fitness is.

“So, a sprinter will be primarily fit to sprint. A footballer will be fit principally to run for 95 minutes each match.

“Whereas the fitness you require in the marines is like a mix of everything, you’ll be doing a sort of anaerobic sprint sessions on a firing range, then you have a quick ten minutes to sort yourself out, and you’ll be off doing some very slow aerobic plodding for two or three hours to get out of the area.

“You have to train for everything. You must be focused on something, which is precisely what this expedition will need.

“The Marines have made me who I am today, and I wouldn’t change anything.

“It’s a career choice if you want to change yourself physically and mentally.”

Why Antarctica? You could have chosen a warmer climate. Why select the most barren and frozen place worldwide to do this challenge?

“It’s probably for that very reason. Look at Everest now, and it’s been well documented that it’s essentially a tourist trap. Putting it plainly and flippantly, in theory, if you have a little mountaineering experience and someone to take everything up for you, you can summit the tallest mountain in the world.

“Regarding people who have been to Antarctica, I think less than 50 people have skied to the South Pole. It’s generally one of the last places that we’re still to fully understand and

“My background trekking in Norway feeds into the knowledge that I could do it.

“It’s challenging, and not many people have done it, whereas other challenges and places have been done quite a lot.”

You’re currently in a bulking phase trying to put 8kg on. Is it just a case of eating what you want right now?

“I don’t actually need to put on that much more weight by the looks of it, but you need a level of body fat reserves to go down there.

“Firstly, it’s insulation. Secondly, the best way of describing it is if you roughly go off nine calories per gram of fat. If I carry 10 kg of extra fat, that’s 9000 extra calories; 100 g daily is 900 calories for 100 days.

“It provides an extra energy source, and then once you’ve run out of glycogen, you metabolize the fat for anything else you want.

“Otherwise, it’s gonna start eating away at your muscles, which is quite toxic for your liver and isn’t great for you if you’re trying to do 30 kilometers of skiing a day.

“That’s why I’m bulking. It’s pretty fun, actually.

“I eat around 3000 calories a day but will need to eat 7000 daily on the expedition, which is double and a bit more on top.

“So it’s quite a big jump mentally and physically to do that.”

What food will you miss the most, do you think, while you’re there?

“I have eggs pretty much every morning for breakfast: eggs and toast.

“I bought some freeze-dried scrambled eggs, which are like American scrambled eggs, quite chunky, and it’s all right, but it’s not the same.

“I love poached eggs on toast. That’s my go-to every morning if I have it in the house.

What’s the most beautiful landscape you’ve ever witnessed, and do you think you’ll see something that will top it in Antarctica?

“It would definitely be Norway. I first saw northern lights during a lecture in the snow in the middle of nowhere.

“As they’re trying to do this lecture, there’s the most beautiful northern lights behind them, and I’m not paying attention. It was the first time I saw that, and I remember it vividly when I think about it now.

“I’ve been to Finland, Sweden and Norway, all beautiful countries, especially in winter. It’s so quiet because there are few people there, you can adequately escape.

“There will be parts in Antarctica where I won’t see anything beyond snow on the horizon for quite a long time because of the earth’s curvature down there, and it’s so relatively flat as you can see things from miles off.

“There’s a small island that’s in the middle of the frozen sea that I’ll be starting on. As you come off that and go on to what would be the sort of a channel between this island and the mainland of Antarctica, you can see the mountains from about 200 miles away.

“Apparently, that’s beautiful because it gives you an aim to keep heading there, and as you go further up it, you see the enormity of what you need to get up.

But then it’s also meant to be a mega view that keeps you motivated, but it never seems to get any closer by the sounds of it.”

Can you stay in contact with your wife and family during the trek? Do you expect the mental side of things to be more challenging than the physical effort?

“I’ll be taking an old school SMS type 140 characters max you can send back and forth, then my family will just download an app here and send 140 character messages back.

“It won’t be every night, and I won’t be on the phone for an hour and a half because that’s really expensive and probably won’t be the best quality, but I’ll try and ring back hopefully once a week to speak to home.

“The biggest struggle will definitely be the mental side of it.

“I was saying the other day that you can train physically and mold your body to do whatever you want, but mentally, I’ve never spent 75 days alone.

“I think the most I did even in training for this was probably three or four days just because Northern Europe is so compact that you’d see someone every two to three days, and then even when you’re not seeing people, there’ll be signs of people.

“It reminds you that there are people around, you’ll see snow tracks, there’ll be ski tracks, or you’ll see animals and know you’re not alone, whereas in Antarctica, there’s nothing.”

What do you want the legacy to be from this? Do you want to inspire others to show there are no impossibilities in life?

“Legacy is a big word. For me, I like adventure.

“My background and military career have led me to this point, but you should never compare your level of adventure to this level.

“This is an extreme way, and some people might have had a bad injury, so walking one kilometer with a dog is their level of adventure.

“It’s about using your body to the level you can and keep having a goal to push yourself towards, and to push yourself not to the level of discomfort, but so you’re uncomfortable.

“If you’re just sitting on the sofa and it’s raining outside, walking in the rain is exhilarating sometimes. Just have a go. It’s good fun. It might be horrible at the time, but when you get back in and have a cup of tea, you appreciate it more.

“In terms of an expedition, this is 500 kilometers further than anyone’s traveled just by skiing before, and no one has ever skied fully across Antarctica.

“There’s another 600 kilometers of ice shelf to get across until you reach the other coast. Depending on how quickly I do it —and if I do it in general—I would know whether it would be feasible to do an entire crossing.

“I want to use this as a platform to get people talking about adventure and access to the cold weather environment.

“It’s such a special place, and many providers—because it’s pretty niche—charge far too much money for what could be made much more accessible.

“So in the next year or two, we want to start doing the guiding, which will be at an accessible price point that’s much cheaper than some of the other providers, purely because we want people to start enjoying it and having this affordable adventure.

“You don’t need to go to more exotic cold weather locations and spend five figures to do this.

“So that’s the other sort of strand you want to start pushing in next year.”