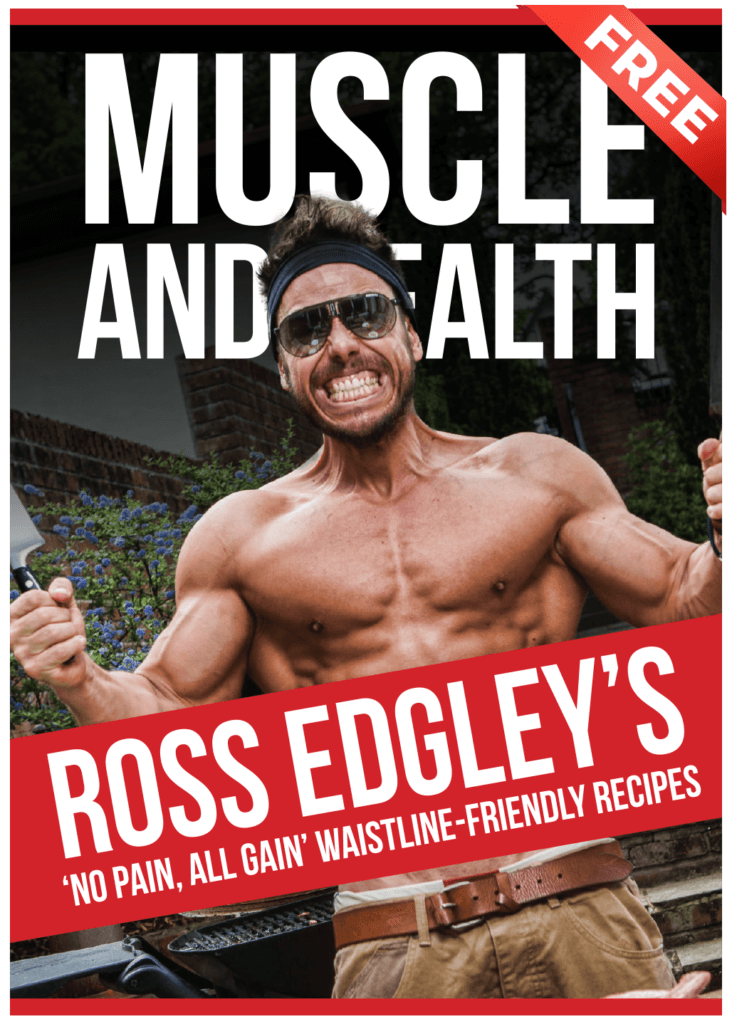

Original article by Danni Levy in Summer 2023 Print Edition

As of January 2023, 6,338 people have reached Mount Everest’s summit.

1,756 are from Nepal. 748 are from the USA. One is from Kenya.

Around 90% of summiters are men.

One of those was blind. One of those had one arm. One of those was missing their right foot.

But not in the history of the world’s tallest mountain has anyone conquered the 8,849 meters without legs.

Hari Budha Magar, the floor is yours.

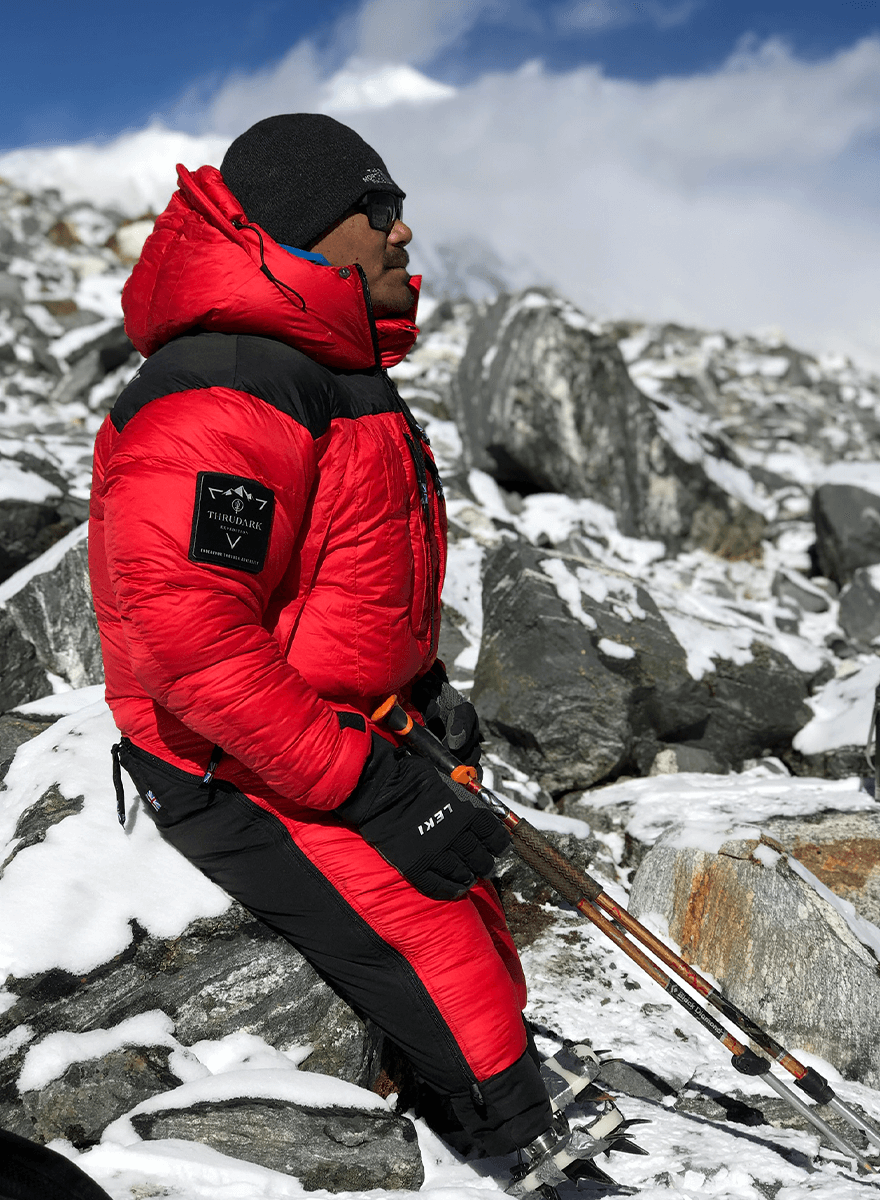

With the support of his prosthetic legs, Magar’s quest is one five years in the making, preluded with world record-breaking ascents of Mera Peak, Mont Blanc and Chulu Far East.

The green light from Nepalese authorities signaled the start of Hari’s inspirational journey on Saturday, May 5th, but his first vertical step, which will eventually lead to the treacherous Khumbu Ice Fall, Geneva Spur and Camp 4 – from where the final charge towards earth’s apex originates – is just another step along a miraculous tale.

It’s a tale of a resilient child born in a cowshed in Nepal, forced into an arranged marriage at the age of 11, all set against the backdrop of the looming Dhaulagiri and Sinse peaks and punctuated by the noise of gunshots reigning down in the ten-year long civil war.

One which defied the overwhelming odds, highlighted by a successful application to join the Royal Gurkha Rifles, but that ultimately ended in trauma with the loss of both legs in Afghanistan.

Plagued by alcoholism, a culturally-embedded shame, and an earth-shattering sense of hopelessness, many would have never recovered, but Hari’s re-emergence into a pioneering beacon of inspiration for disabled people across the globe is remarkable.

Next stop. The top of the world.

Rising from the foothills

In a remote part of Western Nepal lies Mirul, a small village development committee nestled in the foothills of the skyline-dominating Himalayas.

Living was simple at the time of Hari’s birth, with farming and agriculture production growing at an average annual rate of 2.4 percent from 1974 to 1989.

Rice was currency, with many devoting their lives to cultivating the seed to survive – indeed, by 1989, more than three million tons were produced.

Many could not read or write; schools could only offer children chalkstone and wooden planks instead of pen and paper.

Coming from a farming family in Nepal, Hari’s relatives would move cattle across the Rolpa District 2,700m above sea level every two months, which is why he has a unique backstory involving in birth in a cow shed.

Growing up, Hari would walk barefoot to school across the treacherous hills, suffering terrible headaches due to altitude sickness.

But altitude was something that clearly intrigued and fascinated him as a young child, finding the story of traversing Mount Everest a one of wonder, so much so that he would regularly look at black and white pictures of the legendary duo of Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay.

“I grew up in Nepal looking out at the mountains daily. We, the Nepalese people, are very proud of Everest and how Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay were the first to climb it. I was always fascinated by it as a child and longed to reach the summit myself.”

When I was serving as a corporal in the British Army’s Gurkha regiment, I thought seriously about taking it on, but I wouldn’t have had the time to train and prepare.”

By the age of 11, Hari was showcasing the traits of an adult, learning to fend and cook for himself, but the prospect of marriage was likely not on his radar. Marriages in the conservative country of Nepal were traditionally arranged by parents, with many forcing their children to marry for cultural reasons or out of poverty.

In some areas of the country, families marry children as young as one and a half years old. Despite child marriage being illegal in Nepal since 1963 and having one of the highest legal ages of marriage in the world at 20, laws are not adequately enforced, and child marriage rates remain high.

Amidst child marriage, poverty, and poor education, Hari was thrust into a world of war at 17 when a dispute between the Nepalese government and the Communist Party of Nepal began a conflict in February 1996.

Characterized by numerous war crimes, executions, massacres, purges, kidnapping, and mass rapes, the Nepalese Civil War resulted in the death of over 17,000 people upon its cease in 2006.

Whilst most men his age went to fight for the rebels – Maoist Centre – he was fortunate enough to discover the Royal Gurkha Rifles regiment at the age of 19.

Considered to be among the finest infantrymen in the world, Hari’s evident potential was realized when he became one of 230 successful applicants from a pool of 10,000 in 1999.

He would go on to serve across five continents, doing training and operations for the British Army, taking up roles such as Combat Medic, Sniper, and Covert Surveillance.

A second can change everything

After witnessing some of the harshest – and most beautiful – environments globally, Hari was deployed to Afghanistan in 2010. The war in Afghanistan spanned the tenures of three prime ministers and cost the lives of 453 British service personnel and thousands of Afghans.

What was accomplished after 13 years of conflict, which included eight years of heavy fighting in Helmand, remains open to debate. While on patrol, the course of Hari’s existence changed in a split second.

“I can remember everything about the day I lost my legs. We were on patrol with two aims: to familiarise ourselves with a new area and survey and repair a well so that the locals could get water.

“It was mid-afternoon on a very hot, sunny day, and we were told it was safe. I was wearing 15kg of body armor, a radio, water, rations, a first aid kit, ammunition, and a spare weapon by my side. I remember the local children asking us for sweets and stopping to give them some.

“Suddenly, a loud bang and the first thing was a ringing in my right ear. My body armor came up towards my face, my right arm was injured, and I couldn’t move it. I was looking for a tourniquet to stem the blood, and I called for one of my colleagues to help sort me out.

“My right leg wasn’t there; my left was but dangling as skin and bone.”

Hari had stepped on an improvised explosive device, a weapon responsible for the death of 828 troops in Afghanistan between 2010 and 2020, 48.2% of total military deaths.

In the blink of an eye, nothing would be the same. He lost both of his legs above the knee, amongst a plethora of other major injuries.

Upon waking in a hospital bed, negativity and desolation spread throughout his previously watertight mentality. He began to abuse alcohol, regularly mixing it with his medication, and questioned his ability to support his family.

Hari was ashamed to be seen in public because he had grown up in a society where many Nepalese believed that those with disabilities had sinned in a former life and that the disability was a form of punishment or karma. The treatment of persons with disabilities remains discriminatory in many critical areas within Nepalese and Hindu cultures.

In remote rural Nepal, Dalit (so-called untouchable) parents usually do not send disabled girls to school to protect them from discrimination, low expectations and general neglect.

Because of the deep interconnection of disability with religious beliefs, many families do not seek medical treatment or rehabilitation, while some families even attempt to hide the existence of their child’s disability.

“After my injuries, initially, I completely lost confidence. In Nepal, disability was viewed, by most people, as if you’d done something wrong in your previous life and now had the burden of the Earth to carry.”

“Instead of helping people with disabilities, they hide them in a corner. I remember waiting in Kathmandu, and a lady said: ‘You’ve got fake legs. Why don’t you wear trousers, you’d look normal?’ and I replied: “This is normal to me.”

Climbing out of despair

A grueling 12 months ensued following Hari’s life-alternating incident, bookended by a month-long stint in hospital and learning to walk again on his prosthetic legs.

His story is not unique…

Corporal Tom Neathway lost an arm and two legs in a roadside explosion in Afghanistan in 2008. In the agonizing months that followed, the 25-year-old from Worcester fought to walk again with the aid of artificial limbs.

Through sheer determination, he hit a major target when he climbed from a wheelchair and proudly stood to receive a campaign medal from Prince Charles.

As of 2011, one out of every ten veterans was seriously injured at some point while serving in the military, and three-quarters of those injuries occurred in combat, while veterans who suffered major service-related injuries are more than twice as likely as their more fortunate comrades to say they had difficulties readjusting to civilian life.

“Everybody in life has ups and downs, and when they’re low, that’s the time they need help: family, charity, friends, community. It’s make or break. I was privileged to serve in the army and had good prosthetic legs.

“The charity Combat Stress treated me for six weeks. Slowly I started doing sports. Through golf and the On Course Foundation, I started to get my confidence back, and I began to see what I could do physically.”

Not wanting disability to stop him or others from conquering dreams, Hari has been continually working to transform how people with a disability are perceived positively – and how they perceive themselves – ever since.

Since his injury, Hari has battled to rediscover his confidence through various sports and adventures. He has done everything from skydiving to kayaking, cycling, skiing, golf, and climbing.

Hari was the first disabled person to ski in Nepal and was one of the first double above-knee (DAK) amputees to kayak around the Isle of Wight. He holds the world record for being the first ever DAK to summit a mountain over 6,000m.

“Where I was raised, disabled people are considered a burden,” he says. “We’ve deemed a waste of space on Earth. I wasn’t going to spend the rest of my life in a wheelchair. Instead, I went to test myself in Nepal and climbed 4,000 meters.”

Hari has been training for this summit attempt with Krish Thapa, former Chief Mountain Instructor at the SAS and world-renowned climber.

With his help, Hari has already made history as the first double above-knee amputee to trek to Everest Base Camp.

However, reaching the 8,848.86m summit is the ultimate test. The human body is not designed to operate at that altitude. Add to that his own challenges with reduced mobility and speed, and there is a whole new layer of difficulty to navigate.

“One leg I lost about an inch above my knee, and the other around two inches above,” he says. “I now use prosthetic knees when I’m walking, but they’re no good on the mountain because of their weight.

“For climbing, I have what I call ‘stubbies’ that clamp on. They’re effective, but covering ground takes a long time.”

As of May 11th, Hari completed the first phase of his awe-inspiring attempt, climbing to Camp Two before a return to Base Camp to acclimatize.

That alone means he has already become the first DAK to complete the Khumbu Ice Fall and the fastest DAK to climb from Base Camp to Camp One.

Now, the real push toward history begins.

Related article: World’s First Bear Grylls Explorers Camp to open This Month