May 29, 1953. 11.30 am.

Scraping at the snow with his axe, Edmund Hillary chimneyed between a rock pillar and an adjacent ridge of ice to surmount a rocky spur, some 40 feet high obstacle later known as the Hillary Step. Along with Tenzing Norgay, he reached the true summit of Mount Everest, the highest point on Earth.

The men shook hands, as Hillary later wrote, “in good Anglo-Saxon fashion,” before Tenzing clasped his partner in his arms and pounded him on the back. The pair spent only 15 minutes on top, no doubt gazing out at the world below them, unaware of the magnitude of their efforts.

Upon Hillary and Norgay’s historic feat, word quickly spread of the peak’s first conquest: “When we came out toward Kathmandu, there was a powerful political feeling, particularly among the Indian and Nepalese press, who very much wanted to be assured that Tenzing was firs. That would indicate that Nepalese and Indian climbers were at least as good as foreign climbers. We felt quite uncomfortable with this at the time. John Hunt, Tenzing, and I had a little meeting, and we agreed not to tell who stepped on the summit first.” Sir Edmund recalls.

Hunt, a lesser-known cog in the inaugural Everest summit, was the expedition leader, with 320 porters supporting ten climbers.

When the two men made their way back down, the first climber they met was teammate George Lowe, a fellow New Zealander. Hillary’s legendary greeting: “Well, George, we knocked the bastard off!”

Seventy years later, their story remains legendary.

To celebrate another milestone of Everest being toppled, Muscle and Health examines the captivating tale of a mountain that has created legends, made dreams come true, and been the epicenter for a series of tragic accidents and losses.

Safety in numbers

Six thousand three hundred thirty-eight people (as of January 2023) have “knocked the bastard off” since Hillary and Norgay took Everest’s summit virginity.

Once a fabled, mythical achievement shrouded in danger and intriguing uncertainty, 2023’s Everest still possesses eternal wonder, albeit without the charm of its first 50 years in the spotlight.

But by the close of the spring 2002 climbing season, only 1200 climbers had stood atop the world’s loftiest landmark.

Only 19% of those who survived the ‘death zone’ and lived to tell the tale were pre-2003, at an average of 24 climbers per year. Compare that to 2003 onwards, and the sky-rocketing figures are startling. There are 480 summits on average, with 758 attempts per year, meaning approximately 63% of climbers achieved the end goal.

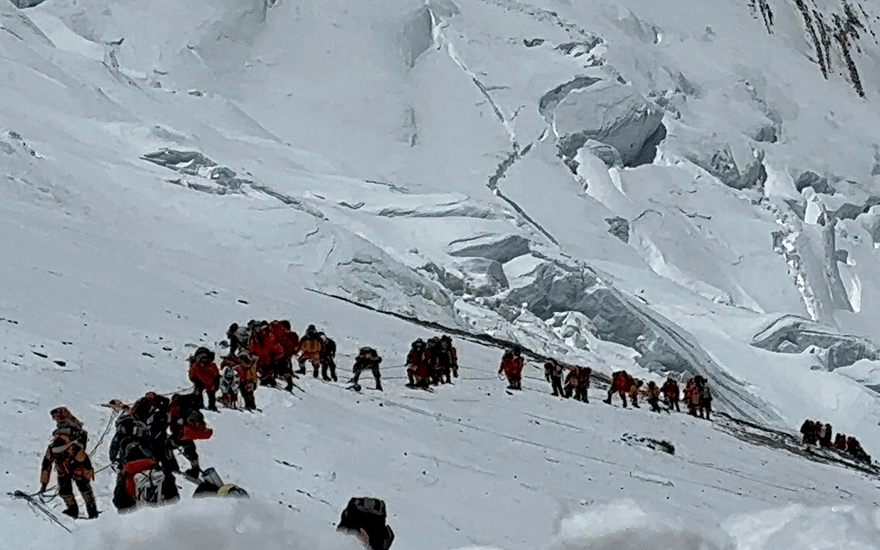

This image by Krish Thapa from Hari Budha Magar’s recent record-breaking summit on 19th May 2023 shows that it’s not the isolated peak you might imagine when you think of Mount Everest.

Credit: Krishala Thapa

But why was there such a dramatic upturn in summit attempts and climbers following the 50th anniversary of Hillary and Norgay’s expedition?

In short, it’s become safer.

Today, roughly 90 percent of the climbers on Everest are guided clients with basic climbing skills. But money talks and clients pay between $30,000 and $120,000, adding to the overcrowding epidemic, which threatens to break the mountain.

Improved weather forecasting has also played a factor in the increase in summits. Previously teams would summit whenever the members were ready. Nowadays, hyper-accurate satellite forecasts mean that teams know precisely when a weather window will open up, and they often go for the top on the same days.

Modern technology, already ubiquitous on Everest—everyone at Base Camp has access to a cellphone or the internet—has also made the mountain safer.

According to a 2020 paper in PLoS ONE, a journal, just 1% of climbers die on the world’s tallest mountain, while the success rate has more than doubled. Between 2010 and 2019, two-thirds of first-time Everest climbers reached the summit, up from less than one-third in the 1990s.

Researchers found that success rates have increased across all age groups. Twenty years ago, climbers in their 60s had just a one-in-eight chance of reaching Everest’s summit; now, the odds are closer to one in three.

The highest number of summits recorded per individual is Kami Rita Sherpa, who has visited the peak for a record number of 26 times, with the accolade for most ascents by a female standing at ten Lhakpa Sherpa.

An open-air graveyard

But while the mountain is undoubtedly safer than when Edmund and Tenzing summited, it’s impossible to ignore the darker reality of Everest, with death and disaster as pervasive as it was since the mountain first spike the curiosity of climbers in the early 20th century.

Some have called it the world’s largest open-air graveyard.

To date, it’s estimated that some 300 people have died climbing Earth’s tallest mountain and that there are approximately 200 dead bodies on Mount Everest to this day.

Bringing back a body requires coordination from a team with perfect conditions, costing $40,000 to $80,000. Few can afford this, though local authorities sometimes pay Sherpas to go up and clear some bodies from the route.

In his recent documentary, ‘Finding Michael,’ Spencer Matthews enlisted an expert team to try and retrieve the body of his brother, Michael Matthews, who plummeted to his death shortly after becoming the youngest Brit to summit the mountain in 1999.

Matthews was not found, but they came across the body of Wang Dorchi Sherpa, a local Nepali guide, and successfully returned him to his family.

In 1999, the body of George Mallory – the oldest known body to ever fall on Mount Everest – was discovered. Mallory’s body was found in a hot spring 75 years after his 1924 death. The English mountaineer had attempted to be the first person to climb Everest, though he had disappeared before anyone found out if he had achieved his goal.

It is still unknown whether Mallory made it to the top, though the title of “the first man to climb Everest” has been attributed elsewhere; rumors of Mallory’s climb had swirled for years. A famous mountaineer, Mallory, was asked why wanted to climb the then-unconquered mountain, he famously replied: “Because it’s there.”

Several high-profile disasters have also blotted the Everest copybook.

In 1970, six sherpas were killed when an ambitious crew set out to create a documentary about Japanese alpinist Yuichiro Miura’s ski descent of Everest.

On April 18, 2014, a team of Sherpas were fixing lines and ladders in the Khumbu Icefall when disaster struck, with a hanging ice block – weighing an estimated 32 million pounds – breaking off and causing an avalanche to barrel right into them. Sixteen sherpas were killed, and the rest of the climbing season was abandoned as many Sherpas boycotted out of respect for the fallen and to advocate for better pay and treatment.

A year later, an earthquake measuring a colossal 7.8 on the Richter scale – the worst in nearly 80 years – set off two avalanches from opposite directions that leveled those at the foot of the mountain, resulting in the death of 22 people.

Perhaps the most high-profile incident came in 1996, when a delay caused a bottleneck at Hillary Step, pushing climbers well past the safe time to summit. A powerful blizzard blasted expedition teams led by Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, and climbers were trapped in precarious positions in the Death Zone, unable to reach safety in whiteout conditions.

Seventeen climbers were stranded in the 1996 blizzard that day, and only half returned. Expedition leaders Hall and Fischer were among those lost, with the event dramatized in the 2015 film ‘Everest’ and documented in John Krakauer’s 1997 book, ‘Into Thin Air.’

Death on Everest is accepted as part of the risk; that is clear.

As of Tuesday, May 23, the death toll on the mountain already stands at ten – with multiple climbers still missing – in 2023.

Unsung heroes

Lesser-known narratives lurk in Everest folklore. Most stories from the mountain continue to focus on the climbers rather than the lives and deeds of multiple mountaineering Sherpas and their families.

Few communities have enjoyed the collective fame and individual obscurity of the Sherpas.

Since Norgay’s ascent, the Sherpas have used his fame and their remarkable abilities at high altitudes to develop a lucrative but heartbreakingly dangerous mountain climbing industry. They have transformed their community, creating wealth and opportunities unthinkable for their grandparents.

But the industry has also taken an enormous toll, with many lives lost and constant family separations. The Sherpas do all they can to keep their wealthy clientele as safe as possible on the mountain; often, these clients become the story rather than the Sherpas themselves.

There are about 114,000 Sherpas living in Nepal and China. Despite this small population, of the approximately 300 climbers who have died climbing Everest, more than one-third have been Sherpas.

Some mountaineers become so obsessed with the glory that they ignore the safety warnings of their Sherpas and press on to the summit without them. As well as carrying oxygen bottles, water and food, Sherpa’s duties include:

- Navigation.

- Setting up camp.

- Managing porters, plus of course.

- All the highly technical climbing skills.

“A job that can encompass not just the duties of a guide and porter, but also those of a butler, a motivational coach, and a lifeguard,”

explains Chip Brown, a writer with National Geographic magazine.

In 2014, Jennifer Peedom directed the documentary, ‘Sherpa,’ which aimed to highlight what a Sherpa guide does—and how devastatingly high their job costs can be to them and their families.

Two of the worst years ever for fatalities were 2014 – which was captured on film – when 16 Sherpas died on the Khumbu Icefall, and 2015 when a massive avalanche engulfed the South Base Camp, killing at least 20, mostly Sherpas.

The Nepali government pockets nearly 20 million dollars in permit fees, leaving a tiny amount for Sherpa guides. While Western Guides make around $50,000 each climbing season, Sherpa Guides make a mere $4,000, barely enough to support their families. Although this is more money than the average person in Nepal makes, their earnings come at a cost – Sherpas risk their lives with every climb.

That level of risk would be too much for the mere mortal among us, non-mountaineering folk who struggle to grasp the concept of throwing their life into the fingertips of the grim reaper.

For them, the physical risks – the avalanches, the frostbite, the verticality, the cerebral and pulmonary edema – outweigh the reward of a successful climb.

But Everest remains the holy grail for thousands, and its magnetic-like pull shows no signs of stopping.

Nepalese government officials issued 478 climbing permits this year, eclipsing the previous record of 408 set during the 2021 season. With over 400 summits in one week – 100 coming on one day alone – those aware of the deaths and missing climbers continue their upward trajectory while blocking out the noise of chaos.

The tragedy is inevitable. The wife of a missing Singaporean climber received a text message notifying her of a successful summit but that her husband “would not be able to make it down.”

The question remains, why risk it all to climb Everest?

“Because it’s there.”