Elite sport and mental health. It’s complicated.

Physical exercise and participating in sports – even for a short time – is a well-documented self-help pill for anxiety and stress.

The endless benefits – both for the body and the brain – are shared, advised and promoted by health specialists, personal trainers, doctors and anyone with or without a qualification.

Yet, so many of the world’s top-performing sportsmen and women in their respective fields have been plagued by depressive episodes over the past decade and beyond. Some even becoming involved in sports scandals.

A 2016 report demonstrated that the population of elite athletes is vulnerable to a range of mental health problems relating to both sporting and non-sporting factors.

The high-profile nature and pressure cooker environments that are unique to the highest performers, offer lucrative rewards and riches, but it’s a deal that comes with baggage.

Intense mental and physical demands are placed on their shoulders, public and media scrutiny rarely ceases, isolation due to constant relocation is common, and injury.

Reputation is placed ahead of rest. Stigma overcomes solace. Brave faces conquer burnout.

One study of 50 swimmers competing for positions in Canada’s Olympic and world championship teams, for instance, found that before a competition, 68% of them “met the criteria for a major depressive episode.”

The research, published in 2013, also found that the incidence of depression doubled among the elite top 25% of athletes. The authors noted: “The findings suggest that the prevalence of depression among elite athletes is higher than previously reported in the literature.”

Ten years have passed since that specific study, so in line with Mental Health Awareness Week, Muscle and Health explores a complicated relationship and the steps that have been taken to offer education and support this generation and the ones to follow.

Suppression can kill

A roar goes up around the Aquatics Centre at the London 2012 Olympic Games as Michael Phelps emerges third along the line of the 4x100m medley American team.

At this point of another dominant games, Phelps’ medals tally at the Olympics was 19, one more than gymnast Larisa Latynina, and he was the all-time record holder of most Olympic medals won.

This is Phelps’ final assault in the pool – before he reversed his decision and competed in 2016 in Rio – alongside Matt Grevers, Brendan Hansen and Nathan Adrian.

Inevitably, America held off the attempts of a plucky Japanese quartet to comfortably claim gold, with the Phelps era rightly receiving a golden conclusion.

You wouldn’t be alone in thinking this would be a time of unadulterated joy and peace for the swimming superstar, but that is where the illusion lies.

In a 2018 interview with CNN, Phelps revealed he “didn’t want to be alive anymore” following his ‘retirement’ from the sport.

Admitting to sitting alone in his bedroom for “three to five days,” Phelps barely slept and wasn’t eating, reminiscing on what he described as his “hardest fall,” after previously revealing he fell into a major state of depression after the games in Athens and Beijing in 2004 and 2008 respectively.

He would go on to receive treatment, and life for him “became easy” as the stigma around his condition lifted.

No longer was Phelps contemplating taking his own life, but instead dedicated to potentially saving those suffering the same sort of emotions.

He implemented stress management into programs offered by the Michael Phelps Foundation, to promote healthy and active lives, especially for children, with therapy and self-care plans which emphasize that it’s okay not to be okay.

Phelps was offered no such option, training under Bob Bowman at the age of 11, with his rapid growth in the pool culminating in him becoming the youngest male since 1932 to make the U.S. Olympic swim team at the 2000 games in Sydney. He was 15 years old.

Research shows that participation in team sports can offer several mental health benefits to kids and teens, including reduced anxiety, depression, and attention problems, according to a study with more than 11,000 participants published in June 2022 in PLoS One.

However, the pressures of high-level and elite competition sports can compound with other issues, such as the pre-existing depression, performance pressure from parents, teachers, and peers to succeed academically and athletically, perfectionism, and unrealistic goals.

Katie Meyer, 22, a soccer goalie at Stanford University, died by suicide in March 2022. The combined pressure of school and sports, along with a fear of potential disciplinary action from school over an incident on campus, may have contributed to her suicide, according to Today.

About a month later, the James Madison University softball star Lauren Bernett, 20, died by suicide. She had just been named Colonial Athletic Association Player of the Week, according to JMU.

Robert Ekne, a German goalkeeper touted to be his national side’s number one at the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, threw himself in front of a train in November 2009 after a long-standing battle with depression.

A much-neglected part of the debate following Enke’s demise was the need to encourage sportspersons to speak up about depression. Not only because the high-pressure situations they face are extremely conducive to the illness but also because they may help millions of other patients by owning up to such illnesses in their capacity as role models.

The case of Enke, while not an example of everything wrong with the modern pressures of sport, does remain an instructive case study on how to improve the handling of athletes at various levels.

Alas, these are just three examples of athletes losing their internal struggle. Only the concept of opening up and talking to someone saved Phelps.

24/7 scrutiny

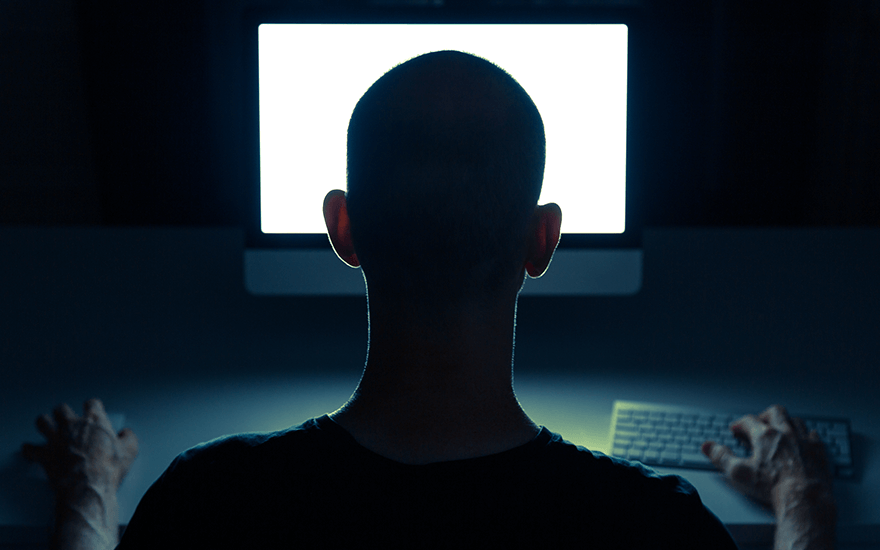

Elite sport is brutal. Failure is common, and career development is uncertain. Of course, injuries, overtraining and concussions can also affect mental health. But an additional factor these days is social media.

A couple of decades ago, sports stars could make mistakes that were the equivalent of bears defecating in the woods, given that no one heard about them.

Now the scrutiny and attention is unrelenting, especially when every phone doubles as a video camera, and every fan has a hotline into players’ brains via Twitter.

It is hard to ignore a bad game or poorly worded comment when met with a 24-hour barrage of bile on social media.

Falling into social media can be the start of a mental health landslide for any elite athlete. Due to its design, addictions can be easily formed, which is largely attributed to the dopamine-inducing social environment that social networking sites promote.

Retweets and likes have become the starting point for assessing performance, highlighting an insecurity and validation process which social media amplifies.

Jordan Speith, a three-time major-winning golfer, has spoken openly about the toxic social media environment: “Just accepting that everything’s in the spotlight, everything’s going to be judged.

“Some people aren’t going to like your swing, the way you grip the club, it’s just everything’s under a microscope too, at least in the golf world, and now extending outwards. I guess accepting that and realizing that everyone has their own opinions, warranted or not.

“I struggle a bit with social media. Trying to quiet the noise there – it’s just people that want to make comments for the sake of commenting — so I’ve just gone away from looking at any comments on Instagram or Twitter. People just want to say stuff just to say stuff. You guys see it everywhere. The hardest part for us now is actually social media.”

One athlete who has faced media pressure is tennis player Naomi Osaka, who withdrew from the 2021 French Open in late May.

According to The Guardian, Osaka first announced that she wanted to skip press conferences for the sake of her mental health and later pulled out of the tournament as a whole.

Osaka explained her reason for withdrawal in a since-deleted Instagram post, stating that athletes are often asked questions that make them doubt themselves, leading to mentally damaging emotions. “I’ve watched many clips of athletes breaking down after a loss in the press room,” she wrote.

Similarly to Osaka, famous American gymnast Simone Biles felt the pressure was too much to continue at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

Biles pulled out of the all-around final and event finals due to mental health issues following an upsetting performance in the qualifying round. As posted on her Instagram, Biles felt she had “the weight of the world on [her] shoulders at times.”

The pressure of being recognized as the greatest ever gymnast would make even the most mentally strong tap out.

It has also been scientifically proven that distractions, including media pressure, negatively affect athletes.

In a study by The Islamic Azad University in Iran, 200 soccer players were surveyed on media pressure: 75% said the media creates stress pressures. The seemingly obvious solution would be to delete any account which invites such high levels of stress. But it’s not simple for athletes.

While ‘celebrities’ in the sporting world can afford to quit social media or have their social media run by someone else, most rely on social media to promote themselves in order to secure or keep sponsorship deals and monetize their brand.

Elite treatment is needed

“On the one hand, athletes are so resilient and do incredible things. On the other hand, athletes are so fragile, and we need to take care of them,” says Emily Clark, PsyD, a licensed clinical psychologist and the associate director of mental health services for the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Experts say we need to change our approach to keeping athletes and everyone else mentally healthy. Because many athletes still don’t know that they can — and should — seek help, they miss out on early intervention and potentially even prevention, says Dr. Clark.

Clark has very specific ways of helping her athletes avoid long-term mental health issues. The United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee now uses two recently developed mental health recognition tools: short-answer questions to help them assess whether the 4,500 athletes they regularly work with are at risk for or already experiencing mental health issues.

The athletes also attend educational programs to help them understand and become aware of mental health issues so they can learn to recognize the signs and symptoms and know when to seek help, ideally before a crisis.

For instance, Clark says she helps athletes learn to differentiate the signs and symptoms of clinical anxiety from ordinary, everyday anxiety because sometimes it can be normal for athletes to feel sadness or fatigue.

The athletes also attend educational programs to help them understand and become aware of mental health issues so they can learn to recognize the signs and symptoms and know when they need to seek help, ideally before a crisis.

What’s clear is the need to start educating athletes from a young age. Early intervention is critical to promoting mental health among youth elite athletes and ensuring timely evidence-based clinical care to those at risk of or experiencing mental disorders.

It is perhaps ironic that the peak onset of mental ill health occurs during the life stage of maximum physical health, at least in high-income contexts.

The latter should never diminish the need to acknowledge and address the former, including in elite competitors.

It is time to focus on the mental health of youth elite athletes. In doing so, the sporting world may identify and unlock new ways to build high-performance environments that promote mental well-being and resilience in the long run.